The ForeHand

Written & Illustrated by Linda

Shaw MBA

THE

NECK

THE

NECK

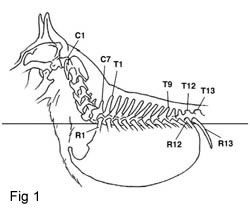

The seven cervical vertebrae (Fig 1, C1 to C7) of the neck

show a slight “S” curve, giving it an elegant, arched

appearance. This provides a sufficiently long neck when

stretched as well as the shorter, more massive muscling

required for strength, the prevention of injury, and the

wide base for attachment of the scapular muscles required to

draw the shoulder forward. An excessively long neck is more

vulnerable to injury in protection, while a short, stuffy

neck makes nosework awkward and tiring. Static head carriage

will be approximately at a right angle to a well laid back

shoulder, or a little higher when the dog is alerted.

Vertical carriage suggests a high, steep wither and topline,

probably due to a low, over-angulated rear. Low carriage may

be due to a roached back sloping down into a low, flattened

wither. Correct head carriage gives the dog an alert, noble

bearing and maximum flexibility in its work.

THE WITHERS

The withers are part of the spine proper, consisting of the

first nine (Fig 1, T1 to T9) of the thirteen thoracic

vertebrae and supporting the first nine true ribs (Fig 1, R1

to R9). The uppermost processes of these vertebrae are

greatly elongated and sloping backward, giving the withers a

sloping profile, forming the highest point of the dog’s

torso and anchoring the scapular muscles required to draw

the shoulder backward.

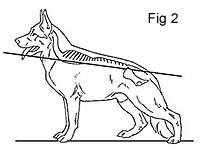

However, the disk portions of

the vertebrae are aligned horizontally in a dog standing

naturally foursquare, and only slightly sloped in a show

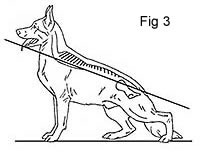

posed dog (Fig 2). Excessively high withers are generally

due, not to longer processes or a straight shoulder, but to

a steeply sloping spine, again resulting from an

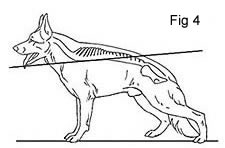

over-angulated rear (Fig 3). Flat withers, which seem

undifferentiated in profile from the rest of the back, may

result from either a high set rear, or from a roaching of

the spine which angles the withers downwards toward the head

(Fig 4). In both cases, incorrectly oriented withers

compromise the ability of the scapula to rotate freely.

THE

SHOULDER

THE

SHOULDER

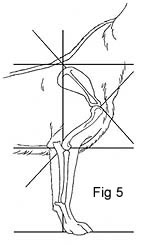

The shoulder assembly is formed by the scapula or shoulder

blade, articulated with the humerus or upper arm (Fig 5). It

is important to remember there is no skeletal attachment of

the shoulder to the body; it rides solely in a bed of

muscle. Hence a very loosely ligamented dog may tend to show

good reach even with an upright shoulder, while mature dogs

with good shoulders, especially males, may show less reach

than they displayed in their youth. Obviously, good

conditioning can help maintain good reach.

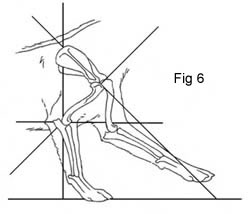

Angulation

of the shoulder is important for free reach, but it is not

true that the static angle of scapula to humerus must be 90

degrees. This is simply because, when the animal is in

motion, its center of gravity drops, the body is lowered

slightly and shoulder angulation at the supporting position

closes to achieve 90 degrees (Fig 6). As well, the shoulder

must carry the greater proportion of the dog’s weight, and

the more vertical the supports, the less energy is consumed

- try standing with your knees bent. Layback is necessary

for motion, but an upright position is necessary for

support. The best performing shoulder will be a compromise

between the two. A 95 degree angle is more than sufficient

to provide ample forward reach, impact absorption and

support. Extreme extension at the trot is not especially

desirable because this is an endurance gait, used to

conserve energy. Maximum extension and energy consumption

should be reserved for the gallop.

Angulation

of the shoulder is important for free reach, but it is not

true that the static angle of scapula to humerus must be 90

degrees. This is simply because, when the animal is in

motion, its center of gravity drops, the body is lowered

slightly and shoulder angulation at the supporting position

closes to achieve 90 degrees (Fig 6). As well, the shoulder

must carry the greater proportion of the dog’s weight, and

the more vertical the supports, the less energy is consumed

- try standing with your knees bent. Layback is necessary

for motion, but an upright position is necessary for

support. The best performing shoulder will be a compromise

between the two. A 95 degree angle is more than sufficient

to provide ample forward reach, impact absorption and

support. Extreme extension at the trot is not especially

desirable because this is an endurance gait, used to

conserve energy. Maximum extension and energy consumption

should be reserved for the gallop.

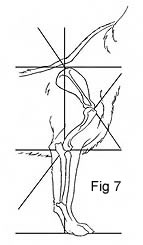

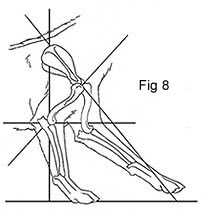

The

scapula is slightly shorter than the upper arm and is not,

unlike the scapula of the horse, capped with cartilage. Its

shortness, combined with its huge area of muscular

attachment, makes it an extremely powerful lever. Despite

the length differential, the greatest efficiency of movement

is achieved when the angle of the upper arm mirrors the

angle of the scapula. A great deal of comment is made by

judges on the slope of a dog’s upper arm, with no mention of

the corresponding angle of the scapula, but I have never

seen an animal with a short, upright upper arm who did not

also have an upright shoulder blade, generally resulting in

a shortened stride (Fig 7, Fig 8). The scapula can be very

difficult to see or feel in a strongly muscled dog, but it

normally mirrors the slope of the upper arm.

The

scapula is slightly shorter than the upper arm and is not,

unlike the scapula of the horse, capped with cartilage. Its

shortness, combined with its huge area of muscular

attachment, makes it an extremely powerful lever. Despite

the length differential, the greatest efficiency of movement

is achieved when the angle of the upper arm mirrors the

angle of the scapula. A great deal of comment is made by

judges on the slope of a dog’s upper arm, with no mention of

the corresponding angle of the scapula, but I have never

seen an animal with a short, upright upper arm who did not

also have an upright shoulder blade, generally resulting in

a shortened stride (Fig 7, Fig 8). The scapula can be very

difficult to see or feel in a strongly muscled dog, but it

normally mirrors the slope of the upper arm.

To

feel the shoulder, locate the groove on either side of the

breastbone of a dog standing foursquare. Immediately behind

this is the point-of-shoulder, the joint between the scapula

and humerus. The humerus slopes from this point to the elbow

joint. The upper tip of the scapula should be directly above

the elbow, at about the second or third thoracic vertebrae.

With the tips of the fingers, one can palpate the spina

scapulae, a sharp, deep ridge of bone that runs the length

of the center of the scapula, and separates the muscles that

draw the blade forwards and backwards. This spine closely

follows the slope of the scapula, not the front or rear

edges of the blade, which is actually quite broad. Many

beginners are surprised to find the scapula is often much

more upright than they predicted from simple observation,

perhaps assuming it follows the black “harness line” that

sometimes runs at a 45 degree angle across the coat of the

shoulder.

To

feel the shoulder, locate the groove on either side of the

breastbone of a dog standing foursquare. Immediately behind

this is the point-of-shoulder, the joint between the scapula

and humerus. The humerus slopes from this point to the elbow

joint. The upper tip of the scapula should be directly above

the elbow, at about the second or third thoracic vertebrae.

With the tips of the fingers, one can palpate the spina

scapulae, a sharp, deep ridge of bone that runs the length

of the center of the scapula, and separates the muscles that

draw the blade forwards and backwards. This spine closely

follows the slope of the scapula, not the front or rear

edges of the blade, which is actually quite broad. Many

beginners are surprised to find the scapula is often much

more upright than they predicted from simple observation,

perhaps assuming it follows the black “harness line” that

sometimes runs at a 45 degree angle across the coat of the

shoulder.

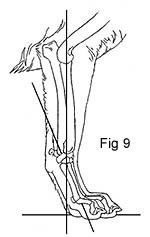

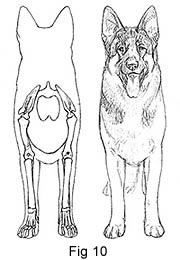

LOWER ARM, PASTERN AND FOOT

The lower arm, or radius/ulna combination, is equal in

length to the upper arm or perhaps a little longer, but

never shorter (Fig 9). It is long enough to give great speed

and jumping ability when necessary, and short enough to give

endurance and resistance to injury. The leg should be

absolutely straight, forward facing and perpendicular to the

ground (Fig 10), but it also has a limited ability to

rotate, increasing agility. A dog’s quality of bone and

muscular condition are immediately apparent in the lower

arm.

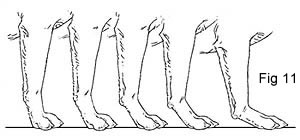

The

pastern, or metacarpals, serves primarily to absorb the

impact of the stride. In jumping, this impact can be

considerable. It is not true that a softer pastern increases

shock absorption. In fact, the softer the joint, the more

easily it compresses and the less absorption is available,

much like old shocks on a car. A straight pastern is capable

of absorbing the most energy, but a small amount of angle,

about 22 degrees, is desirable to ensure that the joint does

not knuckle over on impact. I have illustrated (Fig 11),

from left to right, a cat foot and upright pastern, a

correct foot, two stages of breakdown of the foot and

pastern, and a soft pastern in motion, showing the degree of

breakdown when stress is applied. Some dogs actually drive

their carpal (wrist) pads into the ground while merely

trotting.

The

pastern, or metacarpals, serves primarily to absorb the

impact of the stride. In jumping, this impact can be

considerable. It is not true that a softer pastern increases

shock absorption. In fact, the softer the joint, the more

easily it compresses and the less absorption is available,

much like old shocks on a car. A straight pastern is capable

of absorbing the most energy, but a small amount of angle,

about 22 degrees, is desirable to ensure that the joint does

not knuckle over on impact. I have illustrated (Fig 11),

from left to right, a cat foot and upright pastern, a

correct foot, two stages of breakdown of the foot and

pastern, and a soft pastern in motion, showing the degree of

breakdown when stress is applied. Some dogs actually drive

their carpal (wrist) pads into the ground while merely

trotting.

The pastern also generates

its own propulsive power with each stride. At maximum

compression, fully supporting the dog’s weight, the tendons

running down the back of the pastern and foot are stretched,

gathering energy. Short tendons stretch the most, and the

straighter pastern has the shorter tendons. As the foreleg

moves into the back-swing and follow-through, these tendons

snap like elastics, releasing energy and generating

propulsion. From the front, any tendency for the pasterns to

bend or twist will warp the direction of force, wasting

energy and making the leg vulnerable to injury (Fig 12).

The

forefoot carries a greater proportion of the dog’s weight

than does the hind foot, and is somewhat larger. Each toe is

angled at nearly 90 degrees, elevating the foot over very

thick, absorptive pads. The toes are held closely together,

to better absorb energy and prevent injury. However, the

foot is not catlike, but slightly elongated to give

increased leverage, stride and speed, and the ability to

spread widely in snow or water. The toes are webbed, as much

as any retriever. When standing the feet should point

straight ahead or only very slightly outwards. A working dog

can function reasonably well with minor deviations of almost

any part of its structure, but weak feet and pasterns will

not withstand heavy stress over the long term, especially

that tolerated by guides dogs and police dogs who must work

long hours on asphalt and concrete. After temperament, sound

feet are perhaps a working dog’s most essential tool.

The

forefoot carries a greater proportion of the dog’s weight

than does the hind foot, and is somewhat larger. Each toe is

angled at nearly 90 degrees, elevating the foot over very

thick, absorptive pads. The toes are held closely together,

to better absorb energy and prevent injury. However, the

foot is not catlike, but slightly elongated to give

increased leverage, stride and speed, and the ability to

spread widely in snow or water. The toes are webbed, as much

as any retriever. When standing the feet should point

straight ahead or only very slightly outwards. A working dog

can function reasonably well with minor deviations of almost

any part of its structure, but weak feet and pasterns will

not withstand heavy stress over the long term, especially

that tolerated by guides dogs and police dogs who must work

long hours on asphalt and concrete. After temperament, sound

feet are perhaps a working dog’s most essential tool.